Welcome to the Future!

Why I've started a Substack on the future of the novel

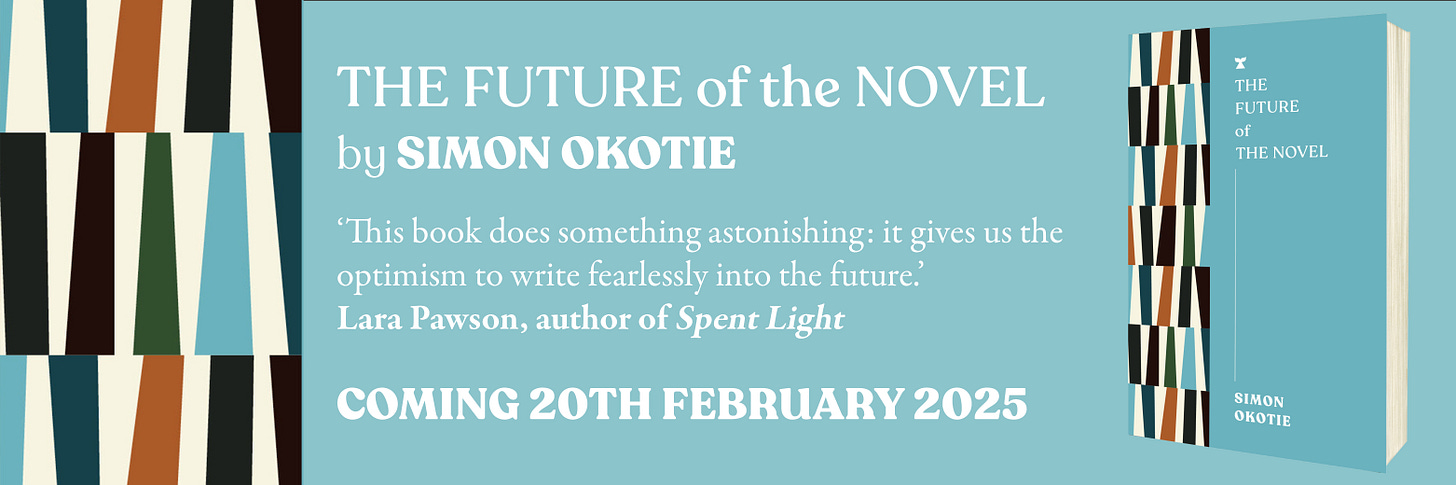

Hello, and welcome to a new Substack exploring the future of the novel. I’m a novelist based in London, and I’ve spent the past couple of years thinking and writing about this topic for a book of the same name (forthcoming in 2025 from Melville House). Mine will be the latest in a long line of titles by working novelists exploring the novel’s future, going all the way back to the great Henry James himself, in 1899.

This Substack will be a space for readers and writers to congregate to explore the novel’s past, present and multiple possible futures. The purpose will not be to try and guess what the novel of tomorrow might look like; instead, we will try to figure out how we want it to look, and how, collectively, we might get there.

One of my starting points is that the future of the novel is dependent on the health (or otherwise) of the ‘anti-novel’. This term for experimental long-form fiction was popularised by Jean-Paul Sartre but can be traced to the writer Charles Sorel, whose novel The Extravagant Shepherd was re-titled L’Anti-roman (The Anti-novel) as far back as 1633. Sorel’s work critiqued all that was conventional in fiction, and championed (as I will here) ‘the need for innovation in the field of literature’.

This will be a place, then, to discuss literary invention in all its forms, and its relationship with more mainstream forms of fiction. After all, if the novel is dependent on the anti-novel to refresh and revive it, then the opposite is also true: the anti-novel has always needed its more popular sibling as a necessary foil – if only to establish an ironic distance from it.

Each week I’ll explore a specific aspect of a contemporary novel – character, voice, setting, etc – and what it might mean for our literary futures. Here are some of the things I’ll look at.

The novelist Rachel Cusk said, a few years ago, that she didn’t think literary character existed anymore, that it is ‘resting on old, possibly decrepit structures’. What, if not character, will be the basis of the novel of the future?

Some novelists attack the continuing emergence of technology without acknowledging that the novel – and writing – are themselves forms of technology. What role will new technologies have in tomorrow’s novel?

Have we actually entered a ‘postfictional’ age, as Timothy Bewes argues in his recent book Free Indirect, one in which the traditional first-, second- and third-person perspectives are abandoned entirely?

I hope you will join me here to explore new forms in fiction.

Free subscribers will get at least one free post a month.

Paid subscribers will get:

one in-depth post a week about innovative novel-writing processes, ground-breaking novels, novelists’ lives and other stuff;

access to my ongoing conversations with agents, publishers, novelists and others about the novel’s future; and

access to our own private chat channel, which is a place to:

meet, greet and compare notes with others who care about the novel’s future; and

ask me any questions (which I will try to answer in upcoming posts).

Founding subscribers will get all of the above, plus a signed and dedicated copy of The Future of the Novel when it is published next year – as well as my undying gratitude.

“The future undoubtedly lies with those who are to-day dissatisfied and experimental…[with those who are] more suspicious of literary traditions, more eager to try out new forms, more exacting in their standards of success.” The Future of the Novel by John Carruthers (1927)