In my Mother’s Room

Reflections on the last few months

I am in my mother’s room. It’s I who live there now. I don’t know how I got there. Perhaps in an ambulance, certainly a vehicle of some kind. I was helped. I’d never have got there alone.

King’s Cross to King’s Lynn, 24 September 2024

I started writing this in my mother’s house, if not (like Beckett’s Molloy) in her room. I’d travelled there by train, using her car for the final leg of the journey from King’s Lynn station to her rural Norfolk village. I had a pile of books by (and about) Beckett on the desk next to me as I started writing: The Complete Short Prose, Nohow On (consisting of the three novels Company, Ill Seen Ill Said and Worstward Ho) and S. E. Gontarski’s Creative Involution, although I wasn’t finding much time to read.

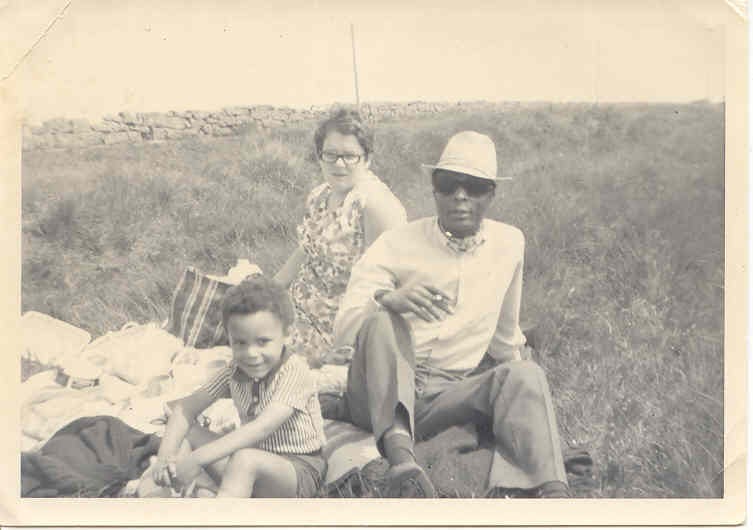

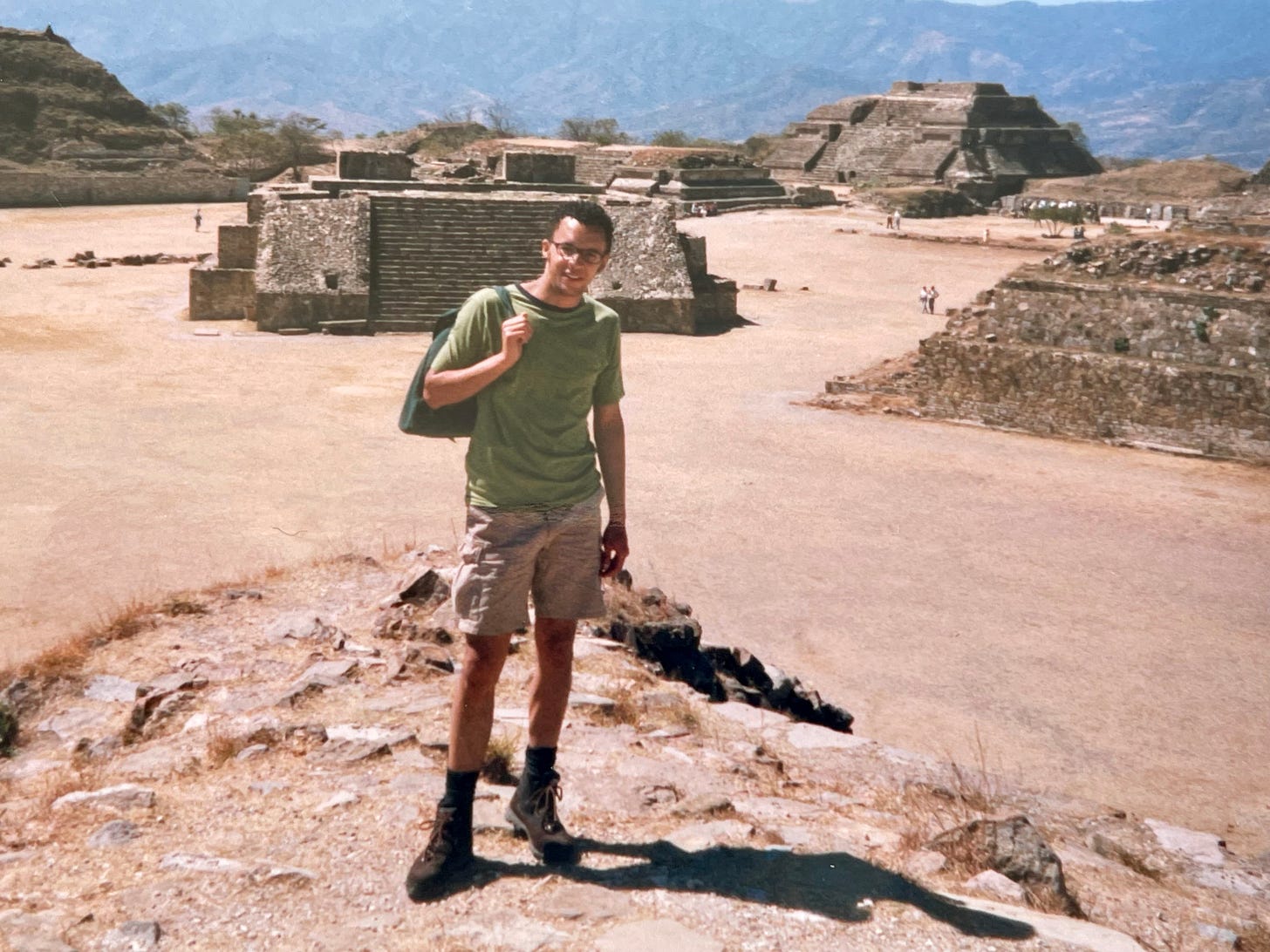

My copy of Nohow On contained a train ticket for the return journey from King’s Lynn to King’s Cross but dated September 27, 1999. At that time I had rented out my flat in London and had been making extended visits to Latin America in between supporting my mum in caring for my dad and grandmother in Norfolk (a period I write about in The Future of the Novel). It was on one of these trips the previous year that I’d resolved seriously to become a novelist. I remember the precise place and moment: the day before Valentine’s Day in 1998 at a café close to the Zapotec archaeological site at Yagul in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. I don’t think the site is much to write home about but the moment was significant for me. It’s where I decided, in between reading Richard Ellmann’s biography of James Joyce, that art was the highest form of life, and that, rather than working when I returned to the UK, that I would be a novelist. I was back in Oaxaca the following year trying to finish my first novel and immersing myself in Beckett’s novella The Lost Ones, James Knowlson’s Beckett biography and The Complete Dramatic Works.

Our domestic situation in Norfolk at the time resembled that of Beckett’s play Endgame, which I’d seen at the Barbican’s Beckett Festival a week or so before making that 1999 rail trip. It opens with the younger character Clov poised in an open doorway stage right, the elderly Nagg and Nell in closed dustbins stage left, and Hamm, their son, stage centre in his wheelchair, initially covered by a sheet. After opening the curtains and uncovering the dustbins, Clov removes Hamm’s sheet to reveal an old man in a dressing gown, a whistle hanging from his neck, a rug over his knees. Clov returns to the doorway, halts, turns towards the auditorium, and says the following:

Finished, it’s finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished. [Pause.] Grain upon grain, one by one, and one day, suddenly, there’s a heap, a little heap, the impossible heap. [Pause.] I can’t be punished any more. [Pause.] I’ll go now to my kitchen, ten feet by ten feet by ten feet, and wait for him to whistle me. [Pause.] Nice dimensions, nice proportions, I’ll lean on the table, and look at the wall, and wait for him to whistle me. [He remains a moment motionless, then goes out…]

Hamm eventually (having woken) blows his whistle, and Clov reappears immediately. In our situation at home, my father would tap too loudly on my bedroom door with the handle of his walking stick to ask if it was time for his painkillers, my mother banging on the kitchen wall when our lunch was ready. My grandmother had died a week and a day before my first trip to Mexico.

I’d picked up Nohow On again after all that time to reread its central story – Ill Seen Ill Said – partly as a way of making sense of what was now my mother’s predicament and partly because I was trying to complete my PhD on Beckett’s late prose works –particularly his ‘closed space’ stories in which characters are confined to sealed geometrical chambers within which they barely move. The old woman in Ill Seen Ill Said is similarly beset by moments of immobility in her isolated cabin.

Heading on foot for a particular point often she freezes on the way. Unable till long after to move on not knowing whither or for what purpose.

This captured something of my mother’s state. She’d asked me to come to her from another part of Norfolk the month before as she’d been unable to move from her kitchen for hours, apart from taking herself the few steps backwards and forwards to a nearby loo, her immobility most likely a side effect of her cancer treatment. I’d been in her house more or less ever since, wheeling her from room to room, concerned about how I was to make a living while effectively also being her main carer.

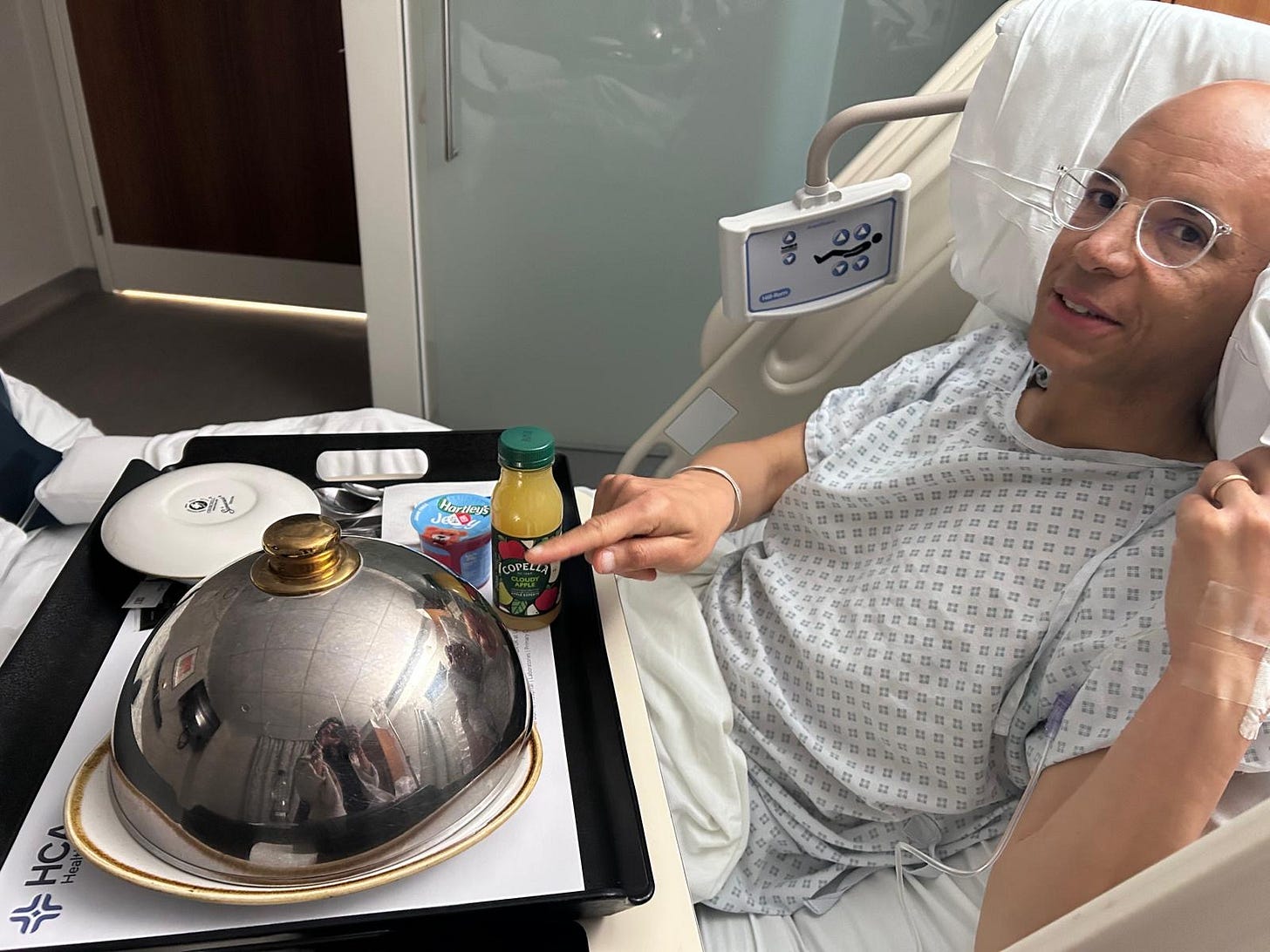

I had cancelled my own doctor’s appointment scheduled for the day after I started writing this piece - the second time I had done so. This was for a recommended PSA test having completed Prostate Cancer UK’s online risk-checker. By the time of my mother’s bone scan at the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital at the start of this year (to check if the cancer had spread) the nurse said we could have had ‘a two-for-one offer’: my own scan, due the same day at the Royal London, had had to be postponed. My own diagnosis had been confirmed the week before.

There is no consensus on what goes ‘Ping’ in Beckett’s closed space story of the same name (to paraphrase the title of a short piece about it by Dan O’Hara). Most interpretations rely on David Lodge’s article ‘Some “Ping” Understood’, an early summary published the year after the story, in 1968. In it, Lodge speculates that the word ‘ping’, which is repeated thirty-four times in the text, might represent the sound of the ricochet of a bullet, or of water dripping, or of a typewriter’s carriage return bell.

Head haught eyes light blue almost white fixed front ping murmur ping silence.

Eyal Amiran interprets Beckett’s text as being about an embryonic recommencement of life, as suggested by its first line:

All known all white bare white body fixed one yard legs joined like sewn.

(Beckett famously claimed to have clear pre-birth memories of being within his mother’s womb according to his biographer James Knowlson.)

For O’Hara himself, however, Ping represents ‘the restricted sensory experience of a hospital in-patient’, one connected to a piece of equipment monitoring the final moments of their life through ‘an unsteady sequence of pings – the echoes of a faltering heartbeat.’ O’Hara bases this on the fact that bedside electrocardiographs, or ECGs, came into standard use in the early sixties – ‘a period when Beckett underwent repeated surgery’ - and just before he started writing these ‘closed space’ stories.

Christopher Ricks’ Beckett’s Dying Words explores similar territory, and this was one of the volumes I took with me on a subsequent trip to Latin America – to Chile in 2000, the year my father died – along with Beckett’s ‘trilogy’ of novels. I spent most of that time in a hut in the foothills of the Andes in the Valle de Elqui, at a Buddhist retreat centre. They were very kind to me, offering me two meals a day and a reduced rate, enabling me to write for extended periods, and I remember joining in with a Buddhist ceremony, one full moon night, even though I wasn’t entirely sure what it entailed. I wrote the Spanish word ‘flojos’ (‘lazy’) on a piece of paper and burnt it, later learning that laziness in the Buddhist tradition can be taken to mean being caught up in the busyness of life to the extent that the most important things get forgotten about.

The significance of that ceremony has been returning to me since I started venturing out again, after my own operation, to the café in my local park where I am editing my new novel; my mum, unable to cope at home, even with our help, is now in residential care. As with all such insights, it doesn’t amount to much in the retelling: that I should stop unconsciously filling my time with activities that distract me from what is most meaningful, which is to say, from trying to ‘give all help and joy to my mothers’ (as the Tibetans say), and from writing – in the fullest sense of the word – writing as a tool, a ‘technology of the self’, to become the person I need, in this lifetime, to become.

Dear Manjusiha, thank you for this moving piece - and get well soon! Love from Akashadevi